Unfair Advantage: The History Of Gerrymandering & Its Impact

Could a few strokes of a pen truly reshape the very fabric of democracy? Gerrymandering, a practice as old as the republic itself, holds the power to skew election outcomes and influence the voice of the people.

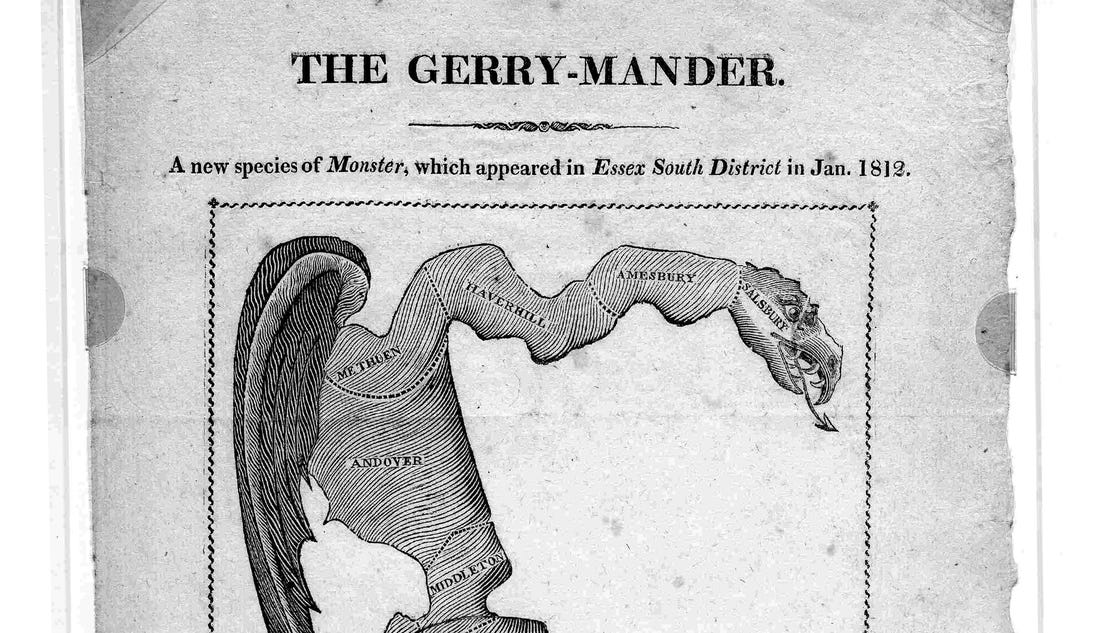

The term "gerrymandering" itself is a fascinating linguistic artifact. Its a portmanteau, a blend of names that speaks volumes about its origins and impact. The "Gerry" refers to Elbridge Gerry, a prominent figure in early American politics, a Founding Father, and later, the fifth Vice President of the United States. The "mander" portion, however, comes from the fantastical world of myth. It is a reference to the salamander. In 1812, while Gerry was Governor of Massachusetts, a bill was signed into law that redrew electoral districts. One particular district, in the Boston area, was drawn in such a contorted way that its shape reminded onlookers of the mythical salamander. This visual association, coupled with Gerry's name, gave birth to the term we use today.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Elbridge Gerry |

| Born | July 17, 1744, Marblehead, Massachusetts |

| Died | November 23, 1814, Washington, D.C. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political Affiliation | Democratic-Republican |

| Education | Harvard University |

| Known For | Founding Father of the United States, Governor of Massachusetts, Vice President of the United States (1813-1814) |

| Career Highlights |

|

| Key Contributions | Advocate for states' rights; involved in the drafting of the Articles of Confederation. His name is linked to the practice of gerrymandering due to the redistricting plan he signed as governor of Massachusetts in 1812. |

| Legacy | Remembered as a Founding Father, a political figure whose name became synonymous with the controversial practice of gerrymandering. |

| Reference Website | The White House: Elbridge Gerry |

The Boston Gazette ran a political cartoon in March 1812, depicting "a new species of monster," a visual representation of the oddly shaped district. An artist, Elkanah Tisdale, famously depicted one of the newly drawn Massachusetts district boundaries as a mythical creature, merging Governor Gerrys name with this fantastical beast, further solidifying the term in the public consciousness. The visual satire served to highlight the perceived unfairness and the manipulation inherent in the redrawing of electoral boundaries.

Gerrymandering, at its core, is the practice of drawing electoral districts to give one party or group an unfair advantage. It's a manipulation of the system, a way to engineer election outcomes through the strategic shaping of district lines. These lines, often drawn by the party in power, can be contorted into bizarre shapes, seemingly defying logic in their quest to achieve a specific political outcome. The goal is to concentrate the opposing party's voters into as few districts as possible, while spreading the favored party's voters across as many districts as needed to secure victory.

The practice is as old as the nation itself. Elbridge Gerry himself, though not the originator, became the namesake for this controversial tactic. The lines of the districts, drawn during his term, were designed to give Gerrys party, the Democratic-Republicans, an advantage in the upcoming election. Gerry, though often associated with the practice, had a complex history, even fighting against the direct election of representatives during his time.

The consequences of gerrymandering are far-reaching. It can lead to a lack of political competition, as districts become heavily skewed toward one party or another. This can result in a decline in voter turnout, as some citizens feel their votes no longer matter. It can also fuel political polarization, as elected officials are incentivized to cater to the most extreme elements within their party, rather than seeking common ground with the opposition. Gerrymandering has been criticized for disenfranchising voters and fueling polarization, shaping the American political landscape in ways that have gone beyond political affiliation.

To understand the impact of gerrymandering, one must look at its various forms. Two of the most common techniques are "packing" and "cracking." Packing involves concentrating the opposing party's voters into as few districts as possible, essentially wasting their votes. Cracking involves splitting up a group of voters from the opposing party into multiple districts, diluting their influence and preventing them from forming a majority in any one district. These strategies, along with others, are used to manipulate district boundaries in a way that benefits the party doing the redistricting.

Gerrymandering isnt always a simple exercise in drawing lines. The process involves a deep understanding of demographics, voting patterns, and political strategy. Those who draw the lines, often referred to as cartographers of electoral districts, weigh heavily on the outcome of elections, understanding the nuanced interplay of data and political maneuver.

The bizarre shapes that can result from gerrymandering are often a testament to the lengths to which political parties will go to secure an advantage. Boundaries can snake and twist, seemingly ignoring geographical features and community boundaries in favor of political expediency. A teacher of civics, William Marx, in Pittsburgh, once pointed out an especially convoluted congressional district, highlighting the absurdity that gerrymandering can produce.

The impact of gerrymandering extends beyond the immediate election results. It can create safe seats for incumbents, making it difficult for challengers to unseat them. This can lead to a lack of accountability, as elected officials may feel less pressure to represent the interests of all their constituents. The practice has been a source of legal challenges for decades, with courts grappling with the question of how to balance the need for fair representation with the political realities of redistricting.

The motives for gerrymandering are clear: to secure or maintain political power. With the stakes being so high, the slightest advantage is perceived as very important for a candidate, and the "cartographers" of electoral districts often weigh on the outcome of an election.

In the United States, redistricting typically occurs every ten years, following the census. This process is often fraught with political battles, as both parties seek to control the redrawing of district lines to their advantage. The power to redraw these lines rests with state legislatures, which often leads to intense partisan competition. This can result in lawsuits and legal challenges, as the losing party attempts to overturn the new maps.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Definition | Gerrymandering is the practice of drawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party or group over another. This often results in districts with unusual shapes. |

| Purpose | To gain a political advantage, either by maximizing the number of seats a party wins or by protecting incumbents. |

| Methods |

|

| Consequences |

|

| Legal Challenges |

|

| Historical Context | Originates from Elbridge Gerry, Governor of Massachusetts in 1812, whose redistricting plan gave rise to the term. |

| Current Status | A contentious issue in many states, with ongoing legal battles and debates about reform. |

The case of Gerrymandering is not only an American phenomenon. It also has international echoes. The strategic manipulation of electoral boundaries is a tactic found in various democracies around the world, with varying degrees of success and controversy. The specifics of the practice, the legal frameworks, and the impact on the electorate may differ, but the underlying principle of seeking to secure a political advantage through the redrawing of district lines remains constant.

| Case | Description |

|---|---|

| Shaw v. Reno (1993) | A landmark Supreme Court case involving North Carolina's redistricting plan, which created a bizarrely shaped majority-minority district. The court ruled that the district's shape raised concerns under the Equal Protection Clause, leading to further scrutiny of race-based redistricting. |

| Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004) | This case challenged a Pennsylvania redistricting plan as a partisan gerrymander. The Supreme Court, in a fractured decision, found that partisan gerrymandering claims were justiciable but did not provide a clear standard for evaluating such claims. The case highlighted the difficulty of establishing a clear legal framework for addressing partisan gerrymandering. |

| League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry (2006) | This case challenged Texas's mid-decade redistricting plan. The Supreme Court addressed issues of partisan gerrymandering and the Voting Rights Act, offering some guidance on the permissible use of redistricting to achieve political objectives, although it didn't provide a definitive standard for evaluating partisan gerrymandering. |

| Gill v. Whitford (2018) | This case challenged Wisconsin's legislative district map, alleging it was an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. The Supreme Court ruled that the plaintiffs lacked standing to bring the case, but the issue of partisan gerrymandering remained unresolved. |

| Rucho v. Common Cause (2019) | The Supreme Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering claims are not subject to federal judicial review, effectively leaving the issue to state courts and legislatures. This decision significantly limited the ability of federal courts to intervene in cases of partisan gerrymandering. |

The question of how to combat gerrymandering has been a subject of debate for decades. One common approach is to create independent redistricting commissions, which are designed to take the task of drawing district lines out of the hands of politicians. These commissions typically consist of non-partisan members who are tasked with creating maps that are fair and reflect the interests of the entire population. States like California and Arizona have adopted independent commissions, and these have often led to more competitive elections.

Another approach is to establish clear legal standards for redistricting. This can involve setting guidelines for compactness, contiguity, and the preservation of communities of interest. Some states have also sought to limit the use of partisan data in the redistricting process, to reduce the potential for political manipulation. Even with these safeguards in place, the courts still play a role in policing redistricting. Challenges to maps are common, and the Supreme Court has made a number of rulings on the issue over the years, though it has often struggled to establish clear standards.

The future of gerrymandering is uncertain. The practice is likely to continue to be a contentious issue, as political parties seek to gain an advantage in elections. However, there is growing momentum for reform, with more and more states considering measures to reduce the impact of gerrymandering. The debate over gerrymandering is likely to continue for years to come, as communities debate the fairness of their electoral processes.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/the-gerry-mander-nypl-726-56a487b85f9b58b7d0d76dbd.jpg)